Brain death is the complete and irreversible cessation of all brain activity, including the brainstem, which is responsible for vital functions such as breathing, autonomous heartbeat and consciousness. When diagnosed according to strict clinical and rigid neurological criteria, it is legally considered equivalent to death in many countries, including the United States. Even if the heart still beat with the help of machines, the body no longer has any potential for recovery — in practice, it is a lifeless organism.

When death isn’t enough: The woman kept alive by force to gestate

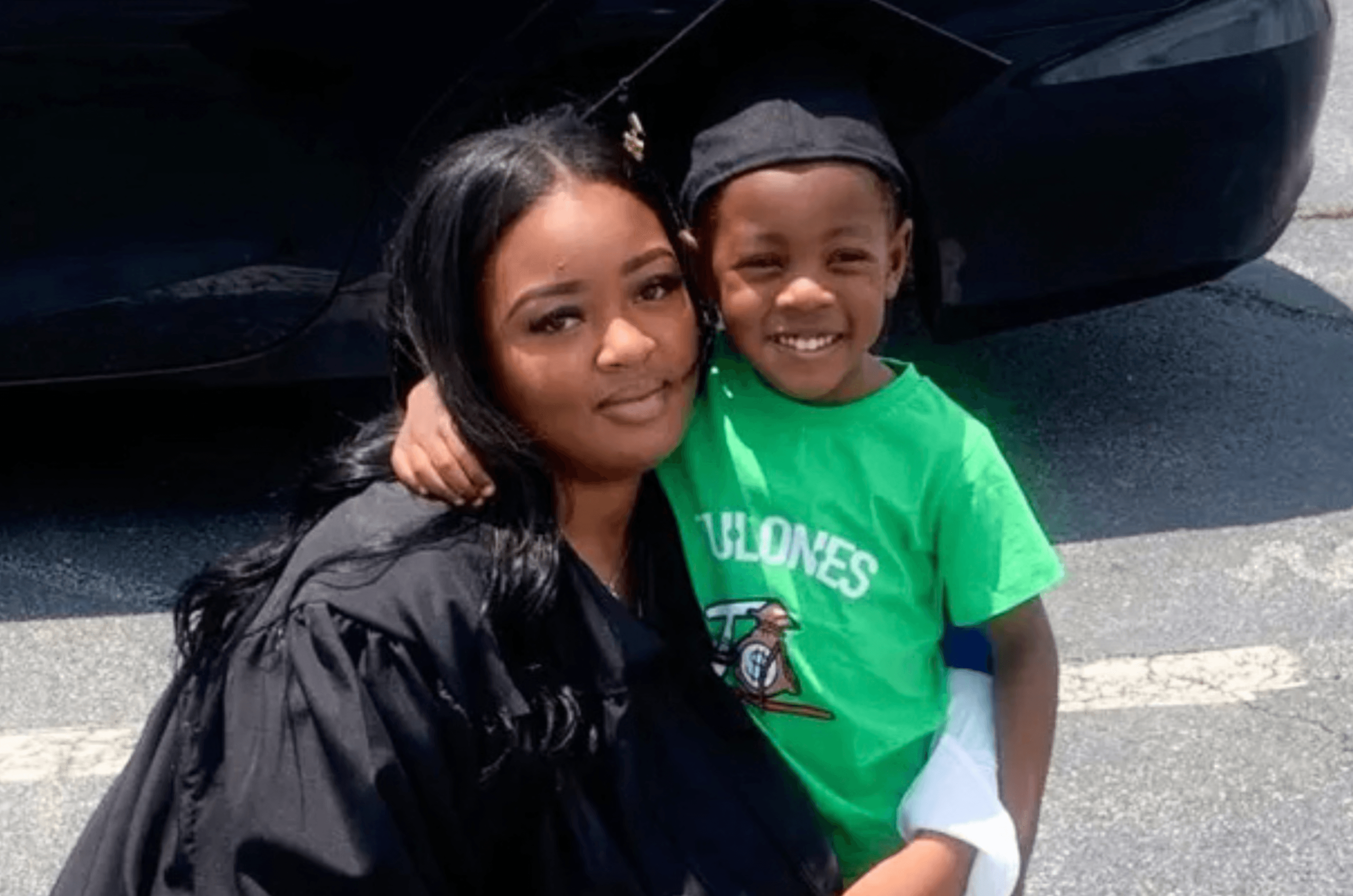

Adriana Smith, a 30-year-old nurse and mother of a 7-year-old boy, was declared brain-dead in February 2025 after suffering complications from blood clots in her brain. At the time, she was approximately nine weeks pregnant. Since then, her body has been kept on life support at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, with the aim of sustaining the pregnancy, accordingto reports from her family.

Adriana’s situation sparked intense debate over the implications of Georgia’s restrictive abortion laws. According to reports from Washington Post and NBC News, although the state’s Attorney General clarified that removing life support from a brain-dead patient does not constitute abortion under current legislation, the hospital chose to maintain life support, citing the need to comply with state laws.

Her mother, April Newkirk, expressed deep anguish over the situation, describing it as “torture” and highlighting the family’s lack of autonomy in making medical decisions on Adriana’s behalf. The case raises complex questions about reproductive rights, bodily autonomy, and the legal interpretations of abortion laws in cases involving brain death.

The case reignites a profound debate on bodily autonomy, reproductive rights, and where we draw the line between life, death, and political control. It also reveals how, in certain U.S. states, the female body can be turned into a kind of “biological incubator” — even against her will and even after life has ended.

Brain death: the end of lide, or not?

As explained earlier, brain death is the total and irreversible cessation of all brain activity, including the brainstem. It is legally considered death in most countries, including the United States. Though the heart may continue to beat with the help of machines, the body has no consciousness or capacity for recovery. It is not a coma. It is not a vegetative state. It is death.

And yet, in Georgia, the presence of an embryo changes everything. The state’s legislation, strengthened after the overturning of Roe v. Wade, restricts abortion from the moment fetal cardiac activity is detected — which can happen as early as six weeks. There are no explicit exceptions for brain death. For this reason, Adriana Smith continues to be treated as a body in use, not as a woman who has died.

Science versus politics

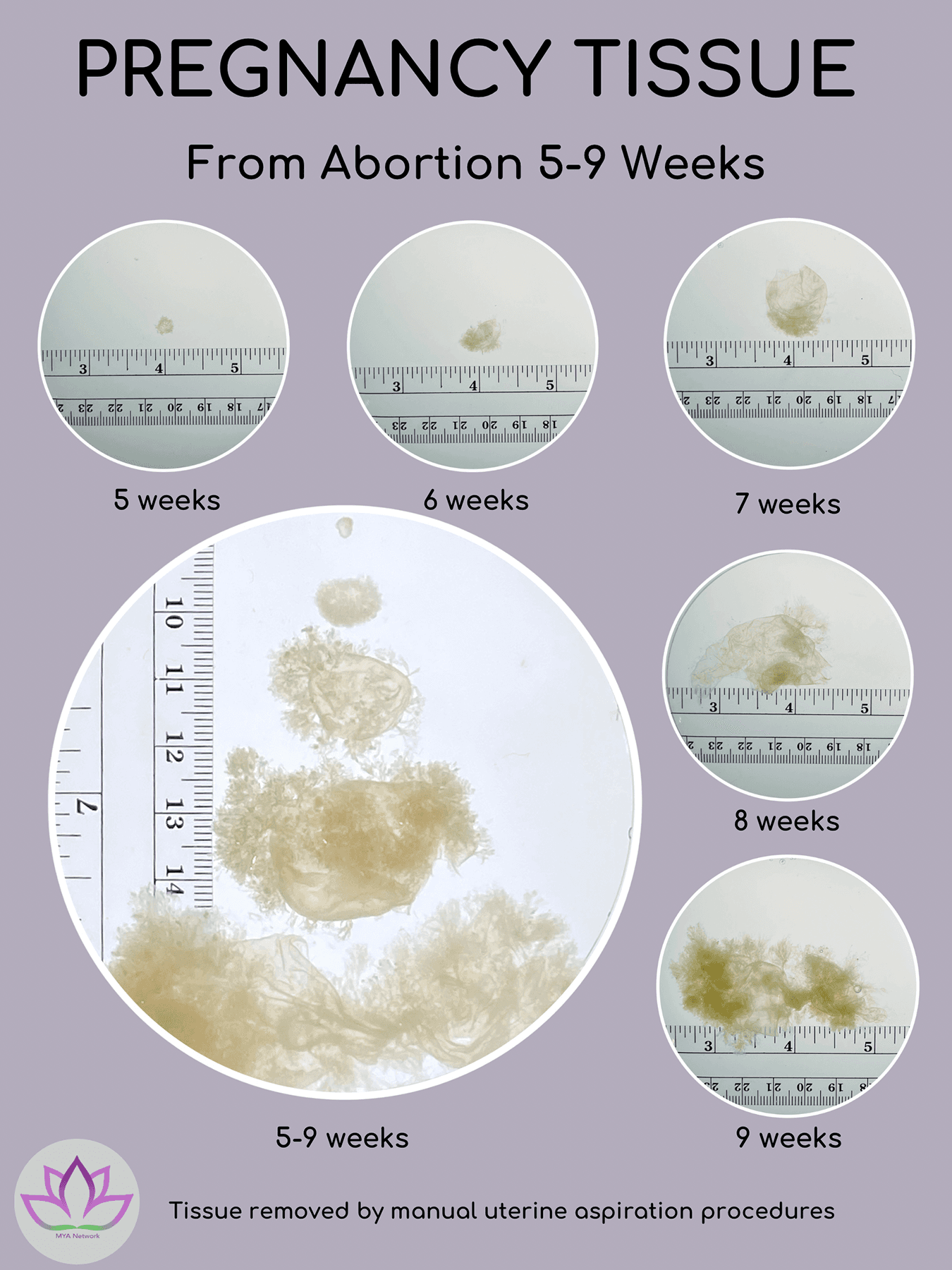

In a video posted on TikTok, OB-GYN Dr. Rachel comments directly on the nine-week gestational stage — the same stage Adriana was in when she was declared brain-dead. She emphasizes that, biologically, it is a cluster of cells that does not yet resemble a fetus, and that it has no developed nervous system or any viability outside the womb. Her argument is clear: it is not only premature, but ethically questionable to subject a body — especially a dead one — to such artificial prolongation to preserve something that, in her words, does not yet represent a developed human life.

She presents an image showing tissue removed during an abortion between 5 and 9 weeks, highlighting what nine-week tissue looks like — the same gestational age when Adriana was declared brain-dead.

Your content goes here. Edit or remove this text inline or in the module Content settings. You can also style every aspect of this content in the module Design settings and even apply custom CSS to this text in the module Advanced settings.

Another powerful video is from Jennifer, an American mother of a teenager who was temporarily kept alive after brain death to donate his organs — something he had expressed he wanted during his lifetime. Still, Jennifer describes the process as painful, traumatic, and exhausting. In Adriana’s case, there was no such expressed wish. Jennifer shares that two years have passed, and the trauma of the experience — being by her son’s side, watching what his body was subjected to in order to keep his organs functioning — still haunts her. The argument is that both instances of life support are meant to save other lives, but in Adriana’s case, that “other life” is a nine-week-old fetus (as previously shown), and the mother’s consent was never given.

When Politics Overrides Humanity

Adriana’s case is not just another entry in the long list of abortion-related controversies. It raises disturbing questions:

– Who owns a woman’s body — even after death?

– What holds more value: a life already lived, or one that is only potential?

– Is it ethical to force a family to keep a dead woman alive for weeks, against their beliefs and emotions?

From a bioethical perspective, Adriana’s case brings into conflict fundamental principles such as autonomy (the right of an individual to make decisions about their own body), beneficience (acting in the best interest of the patient or the fetus), and justice (taking into account the rights of the family, the fetus, and society). When a patient is legally dead, yet her body continues to be used to sustain a pregnancy that may or may not progress, we’re faced with complex questions of defining life, fetal viability, medical intention, and state interference.

The controversy also highlights how medical advancements have intensified these dilemmas. A few decades ago, artificially maintaining the vital functions of a deceased person for weeks or months would not have been possible. Today, with the available technology, it opens a space that is difficult to legislate and even harder to face emotionally for the families involved.

While the case remains ongoing and Georgia authorities maintain their stance, the discussion is growing on social media, in universities, among doctors, legal experts, and citizens. It is an episode that forces society to confront deep questions, for which there are no simple answers — only layers of ethical, human, and legal dilemmas that deserve to be examined with care and sensitivity.