Content discussed in this post

What celiac disease is

Symptoms in children and adults

Celiac disease, gluten sensitivity, and wheat allergy

How diagnosis is made

The role of biopsy and when it can be waived

HLA-DQ2/DQ8: what it’s for

Treatment: the gluten-free diet in real life

Nutrient repletion, follow-up, and goals

Complications and associated conditions

Practical life: school, travel, restaurants, and labels

Quick FAQ

Important notice (health disclaimer)

References and recommended reading

What celiac disease is

Celiac disease is an autoimmune condition triggered by gluten in genetically predisposed people. Gluten is a group of proteins in wheat, rye, and barley. In those with celiac disease, fragments of these proteins activate the immune system in the small-intestinal mucosa, leading to inflammation and villous atrophy. The result is malabsorption of nutrients and symptoms both inside and outside the gut.

Symptoms in children and adults

Presentations vary. Some people have a “classic” picture; others have few digestive complaints.

Digestive symptoms

Recurrent abdominal pain, bloating, gas

Chronic diarrhea, steatorrhea, weight loss

Constipation in some cases

Nausea and vomiting

Extra-intestinal symptoms

Iron-deficiency anemia that is hard to correct

Osteopenia/osteoporosis, cramps, and weakness from calcium and vitamin D deficiency

Delayed growth and puberty in children

Recurrent mouth ulcers, enamel defects

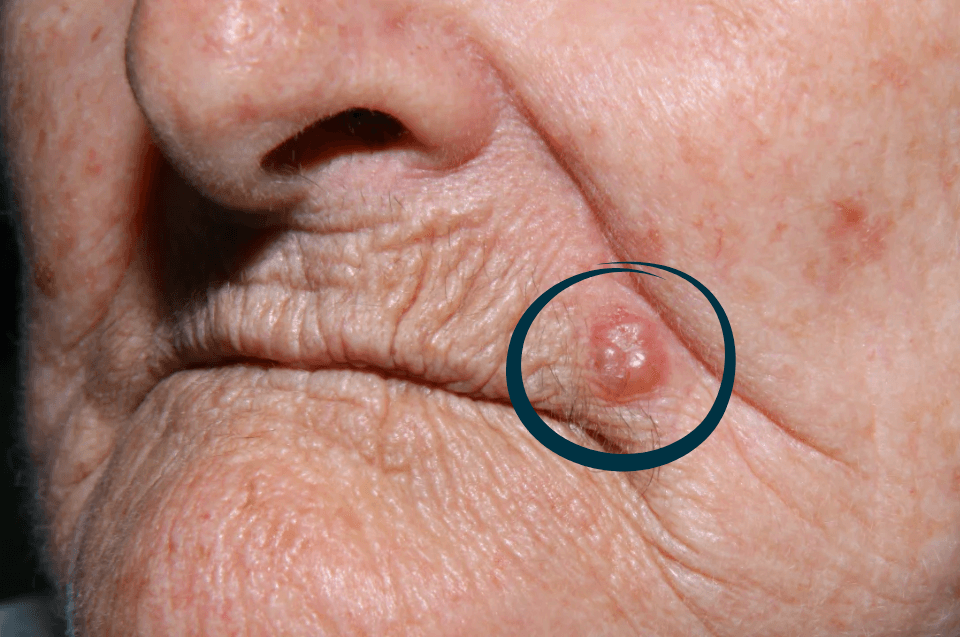

Dermatitis herpetiformis: intensely itchy small blisters on elbows, knees, and buttocks

Fatigue, irritability, headaches

Infertility in some scenarios

Not every symptom needs to be present. First-degree relatives should be screened even if asymptomatic.

Celiac disease, gluten sensitivity, and wheat allergy

These are distinct conditions.

Celiac disease: autoimmune, with villous atrophy and specific antibodies

Wheat allergy: IgE-mediated, usually immediate, with hives, wheezing, or anaphylaxis

Non-celiac gluten sensitivity: symptoms triggered by gluten without typical antibodies or atrophy; management is individualized, often assessing other wheat components such as fructans (FODMAPs)

How diagnosis is made

The most common path combines serology and biopsy. Do not remove gluten before investigation, or tests can become falsely negative.

Key serology

Tissue transglutaminase IgA (tTG-IgA): test of choice

Total IgA: some people have IgA deficiency. If so, use DGP IgG or tTG IgG

Endomysial IgA (EMA): very specific, useful as confirmation

Duodenal biopsy

Performed via endoscopy. It assesses villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia, and intraepithelial lymphocytosis. The Marsh classification describes lesion severity. Biopsy also helps exclude differential diagnoses.

The role of biopsy and when it can be waived

In children, some protocols allow omitting biopsy when tTG-IgA is very high (for example, more than 10 times the upper limit), with EMA positivity on a separate sample and compatible symptoms, after specialist evaluation. In adults, biopsy remains standard in most cases, especially when titers are not markedly elevated or diagnostic doubts exist.

HLA-DQ2/DQ8: what it’s for

Over 95% of people with celiac disease carry HLA-DQ2, and most of the remainder carry HLA-DQ8. The test does not confirm disease, since many in the general population also carry these alleles. Its value is in exclusion: if neither DQ2 nor DQ8 is present, celiac disease is very unlikely. It is useful in equivocal cases, in those who already started a gluten-free diet, or in family screening.

Treatment: the gluten-free diet in real life

Treatment is a lifelong gluten-free diet. This means avoiding wheat, rye, and barley, and products containing malt. Certified gluten-free oats are tolerated by many, but it is best to discuss introduction with the care team, start slowly, and monitor symptoms and serology.

Critical points

Cross-contamination: tiny amounts can inflame the mucosa. Beware of shared utensils, toasters, crumbs on cutting boards, frying oil, porous pans, and airborne flour in kitchens.

Label reading: look for certifications; be cautious with ingredients like malt, malt extract, “flavorings,” and unidentified thickeners.

Restaurants: ask clear questions about preparation surfaces, utensils, and ingredients.

Medications and supplements: confirm with manufacturers whether wheat starch or derivatives are present.

Clinical improvement often appears within weeks, but complete mucosal healing can take months. Consistent adherence is key to preventing complications.

Nutrient repletion, follow-up, and goals

Deficiencies of iron, folate, vitamin B12, vitamin D, and calcium are common at diagnosis. Correcting them speeds recovery.

Follow-up includes:

Reassessing symptoms, adherence, and ongoing education

Follow-up serology at 6–12 months, expecting a fall in tTG levels

Considering bone density testing when indicated

Monitoring growth in children

Reviewing vaccination status, including hepatitis B and pneumococcal vaccines in specific risk settings

Screening for autoimmune thyroiditis and type 1 diabetes when signs suggest

If symptoms persist despite the diet, consider hidden contamination, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), transient lactose intolerance, refractory celiac disease, and other causes. True refractoriness warrants referral to an expert center.

Complications and associated conditions

Osteopenia and osteoporosis, with increased fracture risk

Persistent anemia if the diet is not followed or if there are ongoing losses

Dermatitis herpetiformis

Infertility and pregnancy loss in some scenarios, with improvement after proper treatment

Hyposplenism in the long term in selected cases

Increased risk of intestinal lymphoma and small-intestine adenocarcinoma in untreated or poorly controlled disease

The good news is that strict dietary adherence substantially reduces these risks.

Practical life: school, travel, restaurants, and labels

School and work: communicate with staff and cafeterias; clearly label the person’s food; keep a safe backup snack.

Travel: pack gluten-free snacks, carry translated requests in the local language, and research certified restaurants in advance.

Home kitchen: designate areas and utensils; use dedicated cloths and sponges; store flours in sealed containers and on lower shelves; avoid preparing wheat dough on the same day.

Labels: recheck ingredients with each purchase, since formulations can change.

Quick FAQ

Can I “relax” once my tests normalize?

No. Inflammation returns with re-exposure. The diet is continuous.

Is oats consumption prohibited?

Certified gluten-free oats are tolerated by many. Introduce with guidance and monitoring.

Do I need HLA testing to diagnose celiac disease?

No. HLA helps exclude in doubtful cases but does not confirm disease.

Can children skip biopsy?

In specific situations with very high serologic titers and EMA confirmation, yes—per pediatric protocols. The decision rests with the specialist.

Is gluten sensitivity the same as celiac disease?

No. Celiac disease is autoimmune with typical intestinal injury. Non-celiac gluten sensitivity lacks these markers.

Important notice (health disclaimer)

This content is educational and does not replace medical evaluation. Diagnosis and follow-up of celiac disease should be conducted by qualified professionals. Never start a gluten-free diet on your own before completing the investigation, as this can interfere with testing.

References and recommended reading

American College of Gastroenterology (ACG). Clinical guideline for the diagnosis and management of celiac disease.

ESPGHAN. Recommendations for the diagnosis of coeliac disease in children and adolescents.

British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG). Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of adult coeliac disease.

NICE. Coeliac disease: recognition, assessment, and management.

Ludvigsson JF, et al. The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms. Gut.

Biagi F, Corazza GR. Clinical use of serology in celiac disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

Leonard MM, Sapone A, Catassi C, Fasano A. Celiac disease and nonceliac gluten sensitivity. JAMA.